- Canadian Dividend Investing

- Posts

- Stock and Dividend Analysis: Molson Coors

Stock and Dividend Analysis: Molson Coors

Are beer stocks the ultimate boomer investment?

Let’s start today’s post talking about melting ice cube businesses.

These are businesses that are slowly shrinking into oblivion. Things like the Yellow Pages (rebranded as Yellow Media in Canada, and then, inexplicitly, back to the Yellow Pages), Supremex (TSX:SXP), or Transcontinental (TSX:TCL.A) after it has officially sold its packaging business. That’s still in progress.

Essentially, these companies end up with three options. They can:

Do nothing and pay out every nickel of profits back to shareholders

Do nothing and repurchase as many shares as possible

Use the earnings to acquire other companies — either in the existing sector or branching out into something somewhat related

Of course, companies can use their earnings to do some sort of combination of the three as well, or they could return capital to shareholders in other ways — like paying off debt. Some folks will even include debt payoff in their shareholder yield calculation.

Personally, as you might guess from a guy who calls his newsletter Canadian Dividend Investing, I’m usually a fan of the first approach. My philosophy is that any money reinvested into a dying business generally isn’t good capital allocation. Those earnings should be returned to me, the actual owner of the enterprise, for me to invest how I’d like.

Where this gets tricky is when we talk about businesses that only appear to be a melting ice cube. They might be going through a tricky year or two, or their target market might be suffering. I also think there’s a big difference between a slow decline — one that might take decades to play out — and a business that might only have 5-10 years left.

What should investors do in such a scenario?

Let’s look at one that’s happening today with one of Canada’s oldest businesses — Molson Coors (TSX:TPX.B)(NYSE:TAP).

The skinny

Molson Coors goes back a long way in both Canada and the United States.

Scottish immigrant John Molson started making beer in Montreal way back in the 1780s, eventually perfecting the business in the early 1800s. Not content to dominate the beer business in his new home, he then expanded into various other businesses — including a steamship enterprise and as one of the early partners in Bank of Montreal. Molson eventually served as the bank’s president from 1826 through 1834.

Molson also was involved in Quebec politics, and was instrumental in getting Montreal’s first major hospital built. And if that wasn’t enough, he also played a major role in getting Canada’s first ever railway built. He’s a fascinating guy.

Adolph Coors wasn’t as much of a renaissance man as Molson, but the German immigrant knew his beer. After arriving as a stowaway in the United States in 1868 (and changing his last name from Kuhrs to Coors) he eventually settled into the beer business in Chicago.

A few years later he moved to Denver, bought a share of a brewery there, and bought out his partner in 1880. The Adolph Coors Brewing Company was born, and it eventually grew into one of the largest brewers in the United States by taking an interesting path. For the first 100+ years of Coors’ existence, the company didn’t even bother with the eastern part of the United States. It didn’t stray from the west.

In 2004 the two companies merged, and then purchased the U.S. operations of SABMiller. It has also made dozens of other acquisitions over the years, purchasing small brewers in both North America and Europe. It has also expanded into spirits and into non-alcoholic drinks, although those parts of the business don’t really make up a huge proportion of sales. So we’ll ignore them.

Here’s a glance at some of Molson’s more prominent brands. The drinkers of the group will likely recognize many or all of them. We’ll note that there are dozens more, the company has really diversified over the last couple of decades — and that doesn’t even count some of the brands that have been discontinued.

During the 2010s and into the 2020s, TAP could be characterized as a steady business. It grew a lot in 2017 as it officially welcomed all of MillerSAB’s business into the fold, but for the most part the top line didn’t grow much. Beer was a mature business, and growth mostly came from acquisitions — but was offset by weakness in various mature brands. For instance, after almost two centuries of steady growth, sales of Molson in Canada have struggled. That’s been somewhat offset by growth in other brands — like Coors Light — but Canadians are increasingly moving away from Molson.

There have been a few positive surprises over the years — like when millions of American drinkers boycotted Budweiser products for the company being “too woke” a few years ago — but for the most part beer consumption has been slowly declining. That trend has accelerated as we get deeper into the 2020s, too.

In 2024, overall Molson Coors volumes fell by 5%. North America was even worse than overall company results, with North America falling by 5.7% and the United States falling by 6.6%. Canada was the bright spot, at least compared to weak U.S. results. Western Europe saw volumes decline by 2.6% in 2024, but other parts of the world actually increased their beer consumption. So that helped the Europe/other parts of the world division.

Put it all together, and it translates into a 0.6% decrease in 2024 revenues as both price increases and shifting customer tastes into more premium offerings did offset some of the volume declines.

(Aside: in my time in the grocery business we found that folks are doing this in way more categories than just beer. They were also happy to pay for a more premium product in categories like soda, chips, and, interestingly, pasta. These are treats these days, rather than cheap calories. And so people will pay more for a premium product.)

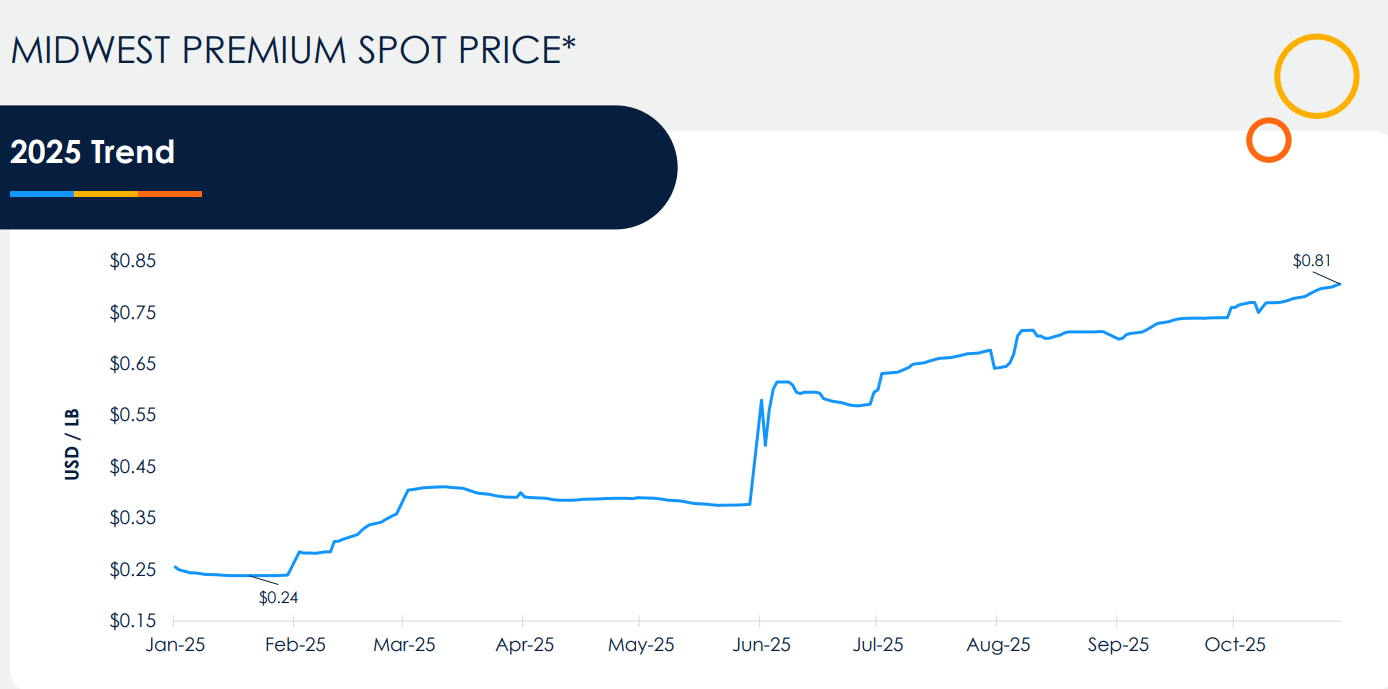

The trend has continued. In its most recent quarter, Molson Coors reported volumes fell by 4.4% in the Americas and 5% in the rest of the world. Cost increases helped, but sales were down 3.5% in the Americas and 2.4% in the rest of the world. We’ll also note that expenses were higher as well, caused by a spike in the cost of aluminum for cans.

Put it all together, and TAP’s results have been kind of crummy. Revenue fell by 3.3% in the quarter and 5.1% in the first three quarters of 2025. Earnings were down by 11.9% and 14.9% in the quarter and year to date, respectively. Per share metrics were a little stronger than the headline numbers, buoyed by a share buyback and lower taxes.

Still, these aren’t great numbers.

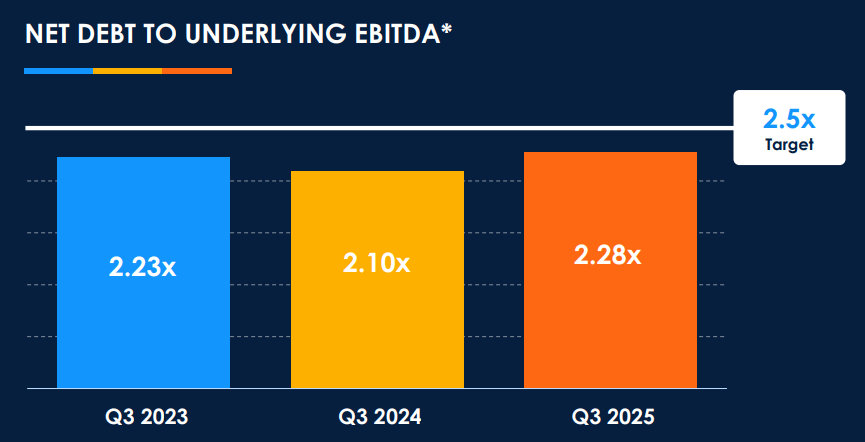

But despite the flat (that’s a beer joke, see?) sales numbers, Molson Coors is doing a few things right. One thing the company is doing is buying up a large number of its shares, which we’ll talk about later. It has also paid back a ton of debt. It owed more than $12B when it acquired all of SABMiller in 2017. These days, that number has trended much lower. Total debt as of the last quarter is $6.5B, and that’s offset by more than $1B in cash. So net debt is a comfortable $5.5B, or a little more than 2x EBITDA. That’s a reasonable amount for a consumer staple stock.

But we will note that the debt-to-EBITDA ratio hasn’t really improved since 2023 as the company has shifted more of its efforts to returning capital to shareholders. EBITDA is also lower as volume declines and higher COGS have eaten into overall profitability.

So, put it all together, and Molson Coors is a struggling company in a declining industry. Beer consumption looks poised to decline even further as the new generation increasingly chooses pot and screen time as their preferred vices. And the short-term looks dicey as well, with the cost of aluminum cans increasing exponentially in just the last year or so. This is not a chart that beer investors want to see.

Still, I think there are some positives happening here. So let’s take a closer look at why someone might be interested in this one — even if beer sales continue to decline.

The opportunity

I’ll quickly mention the short-term reason to be bullish. The price of cans is largely driven by the price of aluminum, which has been doing quite well lately. Admittedly I don’t have much insight into the aluminum market, but generally know that when people start getting super bullish on metals that’s usually the time to sell. I’d say we’re close to that point today, but this is mostly a feel thing. So don’t quote me on it.

The main reason why I believe Molson Coors could be a good buy today comes down to valuation. The stock is cheap, and the stock is really cheap if the company gets any sort of good news that helps overall profitability.

The company hasn’t come out with 2026 guidance quite yet, but analysts expect it to earn a hair over $1.04B in 2026. That’s slightly lower than 2025’s expected bottom line, but it does translate into earnings of $5.54 per share versus an expected results of $5.39 per share in 2025.

This demonstrates the power of a good share buyback — lower earnings overall, but an increase in EPS as the company continues to retire shares.

Some will argue that free cash flow is the preferred mechanism for valuing TAP, and I think those people are onto something. The company should generate a hair over $1.2B in free cash flow in 2026, versus a market cap of $9.5B. That gives us a price-to-free cash flow ratio of below 8x, or a free cash flow yield of more than 12%. Not bad.

And, as I’ve teased approximately 400 times, much of that free cash flow is being returned to shareholders in the form of share buybacks. Molson Coors is also paying generous dividends, and the payout looks poised to continue increasing.

Buybacks and dividends

After Molson Coors got its debt more under control in the latter part of the 2010s and the early part of this decade, it really got to work repurchasing shares.

Shares outstanding peaked at just over 217M in 2021. A few buybacks were made in 2022 and 2023, but the company really started repurchasing shares in 2024. It repurchased 3.3% of shares that year, and has continued pounding the buyback. There were 197.6M shares outstanding at the end of the latest quarter, for a reduction of nearly 10% in the last two years alone.

The company seems committed to repurchasing more shares, too. It spent $332.8M repurchasing shares in the first nine months of 2025. That’s down some from last year, but it’s all part of the $2B share repurchase authorization announced in 2023. That runs through 2028, and should help to support earnings on a per share basis — even if the business itself continues to deteriorate.

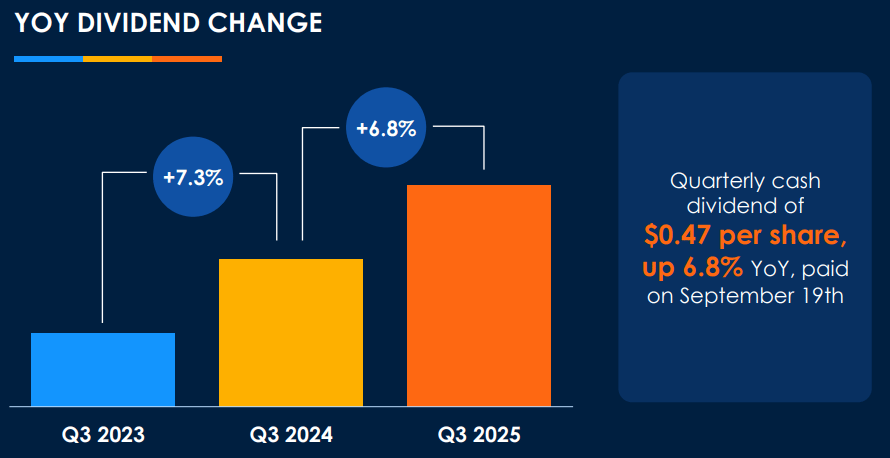

Let’s pivot over to the dividend. The first thing I’ll note is Molson Coors did suspend the dividend in 2020 as a certain ailment ravaged the alcohol business around the world. It then hiked the payout in 2021 and again in 2022, but the dividend remained below pre-COVID levels.

These days, after hiking the payout in each year since 2022, the current payout of the U.S.-listed shares is US$0.47 per share. That works out to US$1.88 per year, or a yield a hair under 4%. That’s still under 2019’s payout of US$1.96 per share, but the growth has been very real.

Molson Coors is expected to do more than US$6 per share in free cash flow in 2026, giving us a very sustainable payout ratio of approximately 30%. That not only bodes well for dividend sustainability; it should also mean that investors will be treated to additional dividend hikes in the future.

In fact, as I’ve argued before, the share buyback will also help make the dividend more and more affordable. If shares outstanding fall by 4-5% per year but the dividend increases by 6%, the actual increase in cash going out the door is minimal. That’s how even a shrinking business like Molson Coors can steadily increase dividends over the long-term. The per share metrics matter.

Dividend safety: High

Dividend growth potential: 4-6%

The bottom line

I started off today’s analysis talking about melting ice cube companies, and how I believe that they should dividend out all their earnings back to shareholders.

At first glance, Molson Coors looks like one of those companies. But I’m not sure it is. Yes, beer consumption is falling in North America and Western Europe, but beer is also a fragmented business. There’s potential for acquisitions or for the company to seize market share from competitors. There’s also potential to shrink the overall size of the company as volumes continue to fall.

And, if that doesn’t work, the share buyback is a nice way to accomplish the same thing. I think the buyback is a terrific use of funds — every share repurchased works out to about a 12% return. Besides, every share repurchased makes the company’s float just a little bit smaller, a outcome that makes an eventual sale all the more likely. I’m guessing we get further consolidation in the beer business over time.

Ultimately, for me, I’d rather focus on parts of the consumer staple industry that I believe will achieve organic growth. The share buyback is nice, and I think the overall outcome will be decent because of it, but I’d rather put my money into something that offers more consistent organic growth. But for the value crowd, this one could be interesting.

Remember, we have a comment section now. Let everyone know how you feel about Molson Coors and leave a comment.

Your author has no position in Molson Coors. Premium subscribers can view his portfolio here. Nothing written above is investment advice. It is for research and educational purposes only. Consult a qualified financial advisor before making any investment decisions.

Reply