- Canadian Dividend Investing

- Posts

- Do More Positions Make a Dividend Portfolio Safer?

Do More Positions Make a Dividend Portfolio Safer?

The case for (and against) ultra diversification for dividend investors

“Hi, my name is Nelly, and I have a problem”

“HI NELLY!”

“Uh, hi. My problem is pretty tame compared to a lot of them, but I still want to talk about it. I own too damn many stocks, but I just can’t bring myself to sell some.”

“Sir, this is an AA meeting. Get out.”

Okay, fine. I guess I have to talk to you guys about my too many positions problem.

For those of you who aren’t premium subscribers and can’t see my portfolio, allow me to give you a bit of a snapshot. I own a lot of businesses.

Like, a lot.

As I type this, I’m currently sitting at 90+ positions.

I’ve been actively trying to sell some of these, but I keep making excuses about why I can’t make a serious dent. I’ll sell something and then find something else to buy. I don’t want to pay the taxes. Or I don’t want to sell what I view as a fundamentally good company when it’s down.

I’m well aware of the downfalls of constructing a portfolio this way. I have some massive winners that have only made me five figures in profit — instead of six figures — because they were sized incorrectly to begin with. A 0.5% position grew into something worth say 1% or 1.2%. It’s nice, but it’s hardly life-changing money.

I always justified it by telling myself that I really just care about the dividends and that capital gains are a bonus. Therefore, more positions equal a safer portfolio from an income perspective. If a company that’s 5% of my portfolio cuts the dividend, it’s a big deal. The same company at a 0.5% weighting is barely a rounding error.

Let’s look at this theory from a more critical perspective, and answer the question once and for all. Are more positions safer than fewer positions? Or is it a case of diworsification?

The case for many positions

The case for owning a bunch of different positions isn’t just more positions = safer, although we’ll focus on that for the time being.

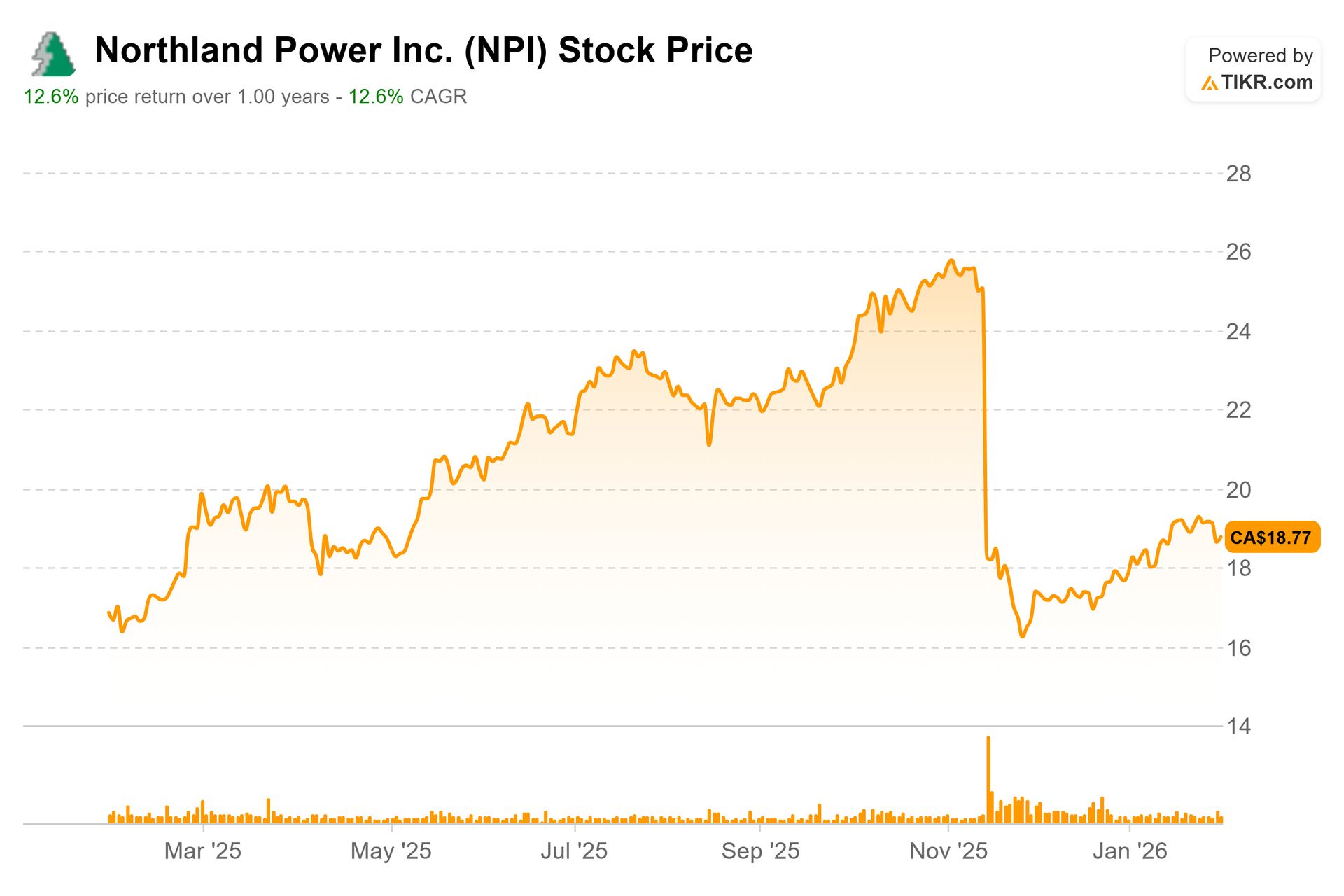

Say you owned Northland Power (TSX:NPI), because you liked the company’s push into renewables, the growth potential from the projects that it currently has under construction, and the fact it is entering into long-term partnerships around the world.

And, because we’re dividend investors, you also appreciated the company’s generous dividend, a payout that looked like it had potential to grow over the long-term as these new projects came online.

And then Northland went and unexpectedly cut the dividend.

The fact is most dividend cuts are telegraphed months or even years in advance. The payout ratio gets worse and worse, earnings are deteriorating, and Twitter is, uh, atwitter with speculation the payout is going bye-bye.

But the Northland one was a surprise. The market anticipated that the company would maintain the payout as its new projects came online, but a new management team decided to slash the payout. And then the stock fell 40% as income investors sold and asked questions later.

Whee!

There have been other surprise dividend cuts over the last few decades. COVID-19 caused temporary disruptions in tons of industries, and management teams did the prudent thing and either cut or temporarily eliminated dividends. BP went from a healthy energy company to one with serious unfunded liabilities when the Deepwater Horizon incident happened. It has since recovered, but it was touch and go for a couple of years there.

I can talk about this from personal experience. In 2020, when COVID punished the stock market, I had shares in various companies that ended up cutting their dividends. A&W was the big one, but at the time I also owned Pizza Pizza and Recipe Corp. And yet, despite these setbacks, my income barely dropped in 2020 at all. In fact, the majority of my portfolio actually hiked their dividends that year, and most of the laggards resumed hiking in 2021 and 2022.

My version of extreme diversification protected me against those dividend cuts, plain and simple.

Owning a bunch of stocks also protects us from our own hubris.

It’s not easy to admit this — especially as someone who runs a stock picking newsletter — but most investors are quite bad at ranking their ideas from best to worst. Their top stock will achieve lackluster results while the one in 6th place will be the one that rockets higher.

If you don’t believe me, do a little experiment. At the beginning of each year, rank your top ideas from one to ten. Write it down, along with the rationale for each. Then, at the end of the year, see how each one performed. Do it again after a second year, just to show the first one wasn’t a fluke.

What you’ll likely find — as I did — is that you suck at ranking your ideas. And sometimes your winners win for completely unexpected reasons.

In such a world, it makes sense to have a more diversified portfolio. As much as we love Warren Buffett and all the wisdom he’s taught us over the years, I think he’s wrong about portfolio concentration. The average investor should put money into their sixth-best idea over more into their top position.

But Nelly. Shouldn’t I just buy dividend ETFs if I want all this diversification?

There’s a case for such a strategy, for sure. But I don’t do it because:

Canadian dividend ETFs have 40-50% exposure to our top financial companies, which I think is a little much. Even if I love me some Canadian banks

SCHD is a terrific choice for U.S. dividend investors, except for one thing — it sells its winners too early, a move which depresses total returns

I can save the fees if I build my own portfolio

Plus, I enjoy the game

Next, let me poke holes in everything I just wrote, and explain to young Nelson what a maroon he was.

Intermission

Bob and I are back. In podcast form.

To be honest, we never really left.

This week on the pod, we discuss Canadian home country bias. You often hear how bad Canadian investors are for this, that we’re maroons for putting so much weight on our local stock market despite it only being something like 3% of the world’s market. But I disagree, and this week we argue that such a bias isn’t really so bad — for a bunch of different reasons.

Find us on Spotify:

Or YouTube:

Or wherever else you might get your pods.

The case for a more concentrated portfolio

As much as we think that more diversification equals a safer portfolio, there are a few different reasons why that just isn’t true.

The first comes down to quality. Like with anything in life, the quality of companies are on a bell curve. There are some businesses that are absolute trash, most that are pretty good, and then a small number of true quality businesses.

I’m never going to be an investor who insists on playing only in the so-called “quality” part of the market, since it tends to be overvalued. There are a lot of folks who are convinced that paying any price for a good business is fine. It’ll all work out in the end.

I’m also convinced a lot of these investors equate a high price with quality. After all, why would a stock go up if it wasn’t quality? So they’re more than willing to buy at all-time highs, but not when shares are 30% lower. I’m much more interested in buying at that point.

Anyway, the point is this. If you own too many stocks, at least some of them are going to be poor quality. Therefore, it makes sense to be selective in the buying process.

The second reason is related to the first. From 2019 through 2022, I bought a lot of different REITs. Sometimes these worked out — like when I bought retail REITs in 2020 — and other times they didn’t, like that time I called Artis REIT my top pick for 2023.

Whoops.

I sold a few of these REITs over the years, but the fact is I still own too many. REITs in each subsector tend to move together, and so diversification is kinda useless.

Now I’ve limited my REIT universe to pretty much a half dozen names that interest me, and that’s about it. I continue to turn over rocks, but I’m mostly adding to those ones as they trade for cheap prices. The rest I’ll sell when the sector comes back in fashion again.

And finally, I’ll make the point about dividend cuts. I’ll make two arguments here.

The first is that a more diverse portfolio actually increases the risk of dividend cuts. The fact is that the more names you add to the portfolio, the greater chance something goes wrong with one or two of them.

But it isn’t just a numbers thing. A more diverse portfolio gives you an excuse to add stocks that don’t necessarily further your long-term goals. You might convince yourself that a deep value pick, or a few ultra-high yielders, or even some of those Yieldmax funds are okay, because they’re only a small part of the portfolio.

Dividend investors tend to define quality a little different than everyone else. We want a stock that will grow both the top and bottom lines, which ultimately leads to dividend growth. And, if you’re me at least, you’re looking for something that also trades at a reasonable multiple.

High levels of diversification give us an excuse to experiment a little, to throw a little you-know-what against the wall to see what sticks. That’s probably not what we want.

What am I going to do?

Ultimately, there’s a lot of space between my current portfolio of 90+ names, and a concentrated one of 5-10 names.

I think the solution for me is somewhere in the middle, with a bit of a bent towards a more diverse portfolio. I’m thinking somewhere in the 50-70 position range is best for me.

I’ll accomplish this by taking a more dividend growth approach to things. I own too many higher yielding names that don’t have much dividend growth potential. Those were important as I embraced early retirement, but should be replaced with more dividend growth. So I’m going to do that.

I’ll also make sure that I limit myself to 1-2 names in a sector when I look at a bombed out area of the market. There will be exceptions when I believe a basket approach works best, but the standard will be to be more selective. Not less.

The first choice will be to add to the existing portfolio with fresh cash, rather than defaulting to a new name.

This will be a longer process. I don’t want to sell everything that doesn’t make the cut instantly one day. I want to add to existing positions when the price is attractive, not willy-nilly.

I was chatting with a subscriber this week who said something I found interesting. He said that pretty much every stock has a buy and a sell price, a point where shares are undervalued/overvalued. I think I’m going to sell a little more when the lower quality parts of my portfolio hit that sell price.

Reply